![[Translate to English:] [Translate to English:]](/fileadmin/user_upload/GRASSI_MAK/01_Museum/Inventar_108721.jpg)

Provenance research

The initial situation

Our museum currently houses around 230,000 individual works of art. All of these pieces have their own individual, but not always clearly communicated, history and provenance.

The digital documentation options available today - in particular the museum database - were unimaginable for a long time. Until the 1990s, the situation was characterized by handwritten inventories, sporadic photographic recording and always fewer staff than necessary to accurately document the collection scientifically.

The holdings acquired between 1873 and 1895, when the museum was run by a private association, are extremely poorly recorded. The project to re-inventory them began around 120 years ago and has not yet been completed. The identification of these objects in particular, many of which are still in existence, was and still is often difficult.

After the end of the Second World War, numerous "confiscated" works of art from castles and manor houses, and later also from expropriations, came to the museum ruins; the conditions under which they were taken over and the form of documentation were often modest. At the same time, the museum suffered extreme losses as a result of looting at the places of removal and confiscation, particularly by the Soviet military.

In the 1960s/70s, the museum built up a large depository of contemporary art for exhibitions abroad. These objects also often remained without an inventory entry for decades.

Overworking of the few employees repeatedly resulted in a loss of information about works of art that had come into the museum.

These few hints may suffice to illustrate that, on the one hand, uncertainties about the provenance of a particular art object can have very different causes and that, on the other hand, the need for research and clarification must be directed both at the pieces in the museum and at the losses.

What have we achieved so far?

Awareness of the need for detailed provenance documentation and verification has developed steadily in our museum since the 1990s. Initially, the creation of documentation folders, which bundle all available material on each individual object, and of course the gradually developed museum databases were helpful.

In the 1990s, the issue of restitution of land reform art came to the attention of the museum. It required an intensive review and examination of the inventory and led to numerous restitutions and amicable settlements.

Shortly afterwards, a critical review of all objects acquired between 1933 and 1945 was carried out by external experts. This revealed hardly any significant evidence of unlawful acquisitions.

We dealt intensively with the losses at the places of removal and the confiscations by the Red Army. As a result, works of art that had mistakenly ended up in the Dresden State Art Collections (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden) were recovered for Leipzig and evidence of looted art from our museum still in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow was provided.

In our inventory catalogs and in the labeling of our exhibitions, we were pioneers in Leipzig in identifying all known provenances.

In the mid-1940s, we returned Bauhaus graphics from other museums that had been confiscated in the course of the "Degenerate Art" campaign to their original owners without much fuss (which, by the way, is still not common practice in the German museum landscape).

In 2015, we published detailed documents about the events in our museum during the Nazi era in the volume "Die Museumschronik 1930 bis 1945". The follow-up volume, which covers the years 1946 to 1960, is already available. This makes the actors, places and processes of numerous important acquisitions tangible.

Our scholars have undertaken detailed research into prominent individual objects - such as the della Robbia Majolica Madonna, which was once purchased for Hitler's Linz museum project and is on loan to us from the Federal Republic of Germany - and we pass on the results of this research to our visitors.

In 2018, we decided to repurchase and partially restitute a bundle acquired in 1936 at the auction of the Margarete Oppenheim Jewish collection by making a compensation payment to her heirs. The process was completed in 2021.

And although the topic of objects looted by colonialism is mostly one of ethnological museums, we are currently involved in a research project investigating whether Chinese artworks that came into the European art trade after the Boxer Rebellion in the early 20th century are in German museums (see below).

Outlook and further projects

Our most important goal is to set up an online object database that will contain all of the museum's existing objects as well as those that have been lost. This is the only way to ensure transparency and accessibility of all information for all interested parties and researchers. A first block of this online collection will be accessible this year, but the overall project still requires a lot of energy, personnel, time and money. We are hoping for funding and cooperation partners.

The greatest need for research currently exists for art objects that came into the museum between 1946 and the mid-1990s. During this period in particular, the provenance of the pieces was often little questioned.

However, our research interest is also focused on pieces that no longer exist, such as objects that were lost around 1945 as well as many hundreds of pieces that had to be handed over to the art trade by order of the GDR Ministry of Culture from the early 1960s onwards.

Traces of the "Boxer War" in German museum collections

a joint approach

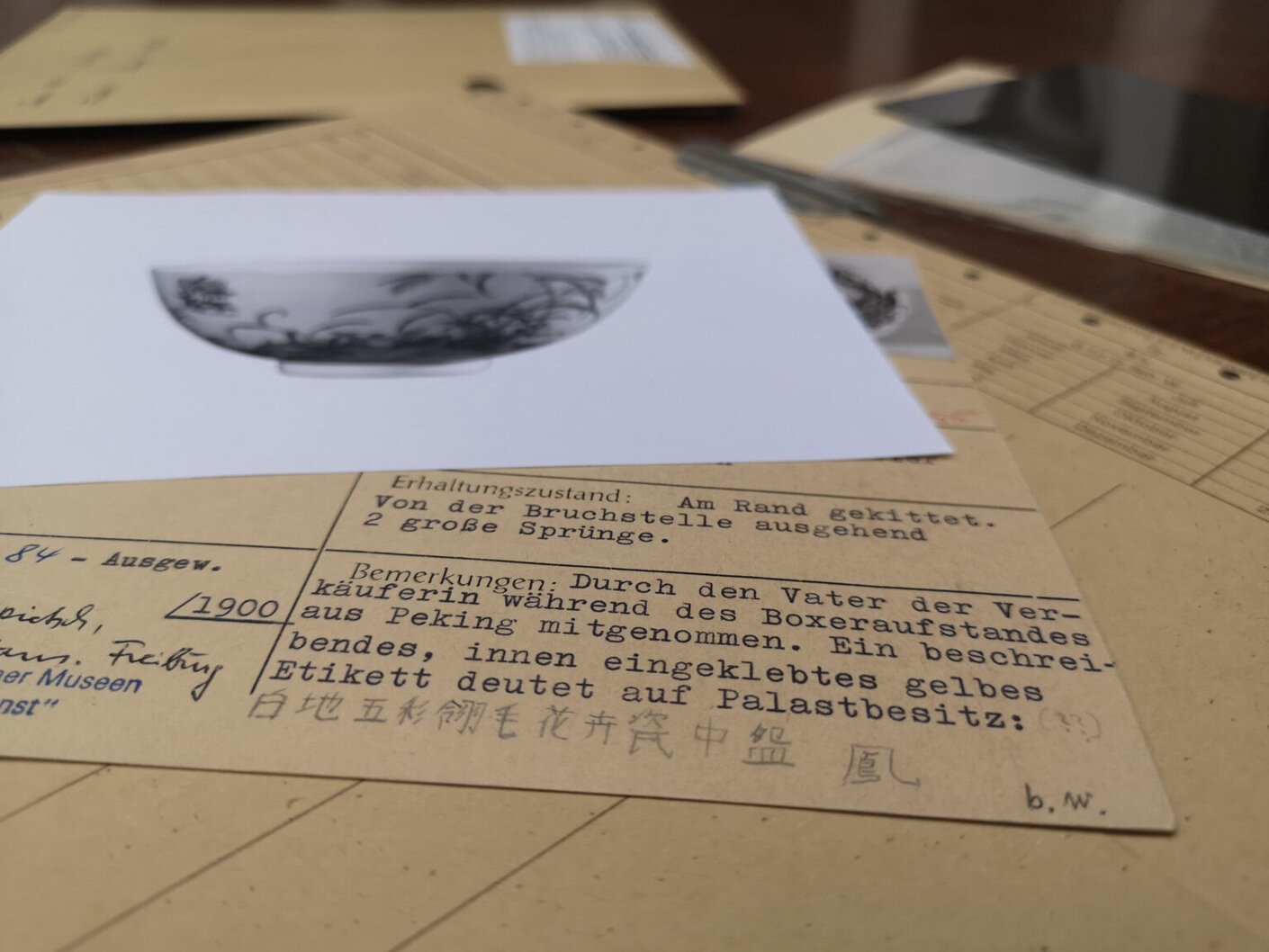

Porcelain, bronzes, scrolls - hundreds of objects from China in German museum collections originate from looting that took place around 1900 in the context of the so-called "Boxer War". Their problematic provenance is known in very few cases, and the various ways in which they ended up in German collections have only been rudimentarily researched. For the first time, seven German museums, under the direction of the Zentralarchiv (Central Archive) der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, are joining forces in this project to systematically survey their holdings for looted items from the Boxer War and to jointly research their provenance in cooperation with the Palace Museum in Beijing.

At the end of the 19th century, fighters known in Western literature as "Boxers" were the driving force behind an anti-imperialist movement in northern China called Yìhétuán Yùndòng (義和團運動, Movement of Associations for Justice and Harmony). The insurgents initially attacked Christian missionaries and their Chinese followers, and soon also foreign entrepreneurs and diplomats. In May 1900, the violent riots spread as far as Beijing and culminated in a siege of foreign embassies in June. An eight-nation alliance, which included the German Empire, sent troops to China. During the so-called "Boxer War" of 1900-1901, not only were the rebels crushed in the most brutal manner, Beijing was also looted and pillaged. Thousands of works of art and other artifacts from the looting subsequently found their way into German museum collections, either directly or indirectly, for example via the art trade, where they are still kept and exhibited today.

The project "Traces of the Boxer War in German museum collections" examines both objects in the individual institutions and the actors involved in their looting, transportation and trade. The aim is to make the historical mechanisms of collecting these sensitive objects in Germany visible across museums. In addition to researching the collections, the aim of the project is to publish a methodological guide. This will create the basis for a more comprehensive analysis of the Chinese collections in national and international museums in the context of the "Boxer War".

Museums:

Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Museum am Rothenbaum – Kulturen und Künste der Welt Hamburg

Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg

GRASSI Museum für Angewandte Kunst Leipzig

Museum Angewandte Kunst Frankfurt am Main

Museum Fünf Kontinente München

Project management: Dr. Christine Howald

Research assistant: Kerstin Pannhorst

Cooperation partner: Palace museum Peking

Project funding: German Lost Art Foundation (Project-ID: KK_LA03_I2021)

Project term: November 2021 until November 2023

Explanatory films on provenance research

The German Lost Art Foundation has published three vividly animated explanatory films on key topics of provenance research. They provide answers to the following questions:

The links lead directly to the films on YouTube (German only).